Guest Post: Underload: Today’s Problem of Internet Congestion Control

Guest blog post by Michael Wezl (Full Professor at University of Oslo, Norway) discussing the use of Measurement Lab’s Neubot data to research Internet congestion control.

Internet congestion control mechanisms were initially designed for scenarios where networks are overloaded, i.e., sending rates would be either moderate or large compared to available link capacities. Moreover, it has been common to assume that applications produce long, “greedy” flows, which are able to saturate a path’s capacity over time.

Things have changed. Over the last two decades, Internet capacities have grown vastly, and since the 2010s, social networking applications – not only web-based, but also real-time gaming, video conferencing and messengers – have become ever more popular. Web sites, messengers and games produce transfers which usually need only a handful of packets. One-way video such as Netflix often consists of short bursts with long pauses, and the rate of an interactive video or audio application is commonly limited by the codec.

With these applications, even the most modern Internet congestion control algorithms struggle to obtain feedback about the path’s capacity limit, often causing them to transmit data at a rate that is unnecessarily low.

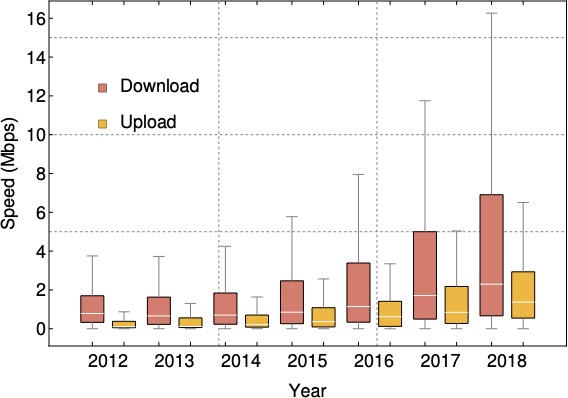

Our recent article [1] uses data from Measurement-Lab’s Neubot tool [2] to make the point that the above problem of “underload” is bound to become worse. Figure 1 shows Neubot data that were collected from 2012 to 2018 in over 90 countries. Neubot ran daily in the background of up to 4500 static volunteer user computers and periodically tested the network performance. Some values are very small because many of the countries in the study have poor Internet connectivity. The lower and upper ends of the boxes in the figure represent the 25% and 75% percentiles, respectively. Outliers are not presented for the sake of clarity.

Figure 1: Neubot data from 90 countries from 2012 to 2018 show that the upper end of transfer speeds increases faster than the lower end. A similar figure in [1] also depicts data from 2019 to 2021 which we omit here because Cubic was enabled in Measurement-Lab in 2019. This caused a surge in throughput which makes the effect harder to see.

From Figure 1 it is clear that, across these 90 countries, the upper end of transfer speed grows much faster than the lower end. This is because, across the world, it appears that low-end connectivity does not disappear just as quickly as the high end improves – or, in other words, the various countries of the world upgrade their networks at a different pace.

Congestion control, however, is commonly designed to operate end-to-end, and its behavior (e.g., the initial window that is used) is expected to follow a uniform worldwide standard. As a result, congestion control algorithms of protocols such as TCP and QUIC see an increasingly large operational space in which they do not obtain any capacity feedback at all.

As a way out of this dilemma, our article suggests to step away from the strict adherence to an “end-to-end” design of congestion control, and instead consider replacing it with selective per-segment mechanisms that are customized to their operational environment. Doing so will require research – and we highlight some possible future directions in [1].

Biography:

Michael Welzl is a Full Professor at the University of Oslo, Norway. His research interests include transport protocols, congestion control, performance evaluation, Internet architectures and energy efficiency.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my co-authors Peyman Teymoori, Safiqul Islam, David Hutchison, and Stein Gjessing for their contributions in [1].

References

[1] M. Welzl, P. Teymoori, S. Islam, D. Hutchison and S. Gjessing, “Future Internet Congestion Control: The Diminishing Feedback Problem,” in IEEE Communications Magazine, September 2022, doi: 10.1109/MCOM.006.2200008.

[2] J. C. De Martin and A. Glorioso, “The Neubot project: A collaborative approach to measuring internet neutrality,” in IEEE ISTAS, 2008.